Optics

Polarization Interferometry

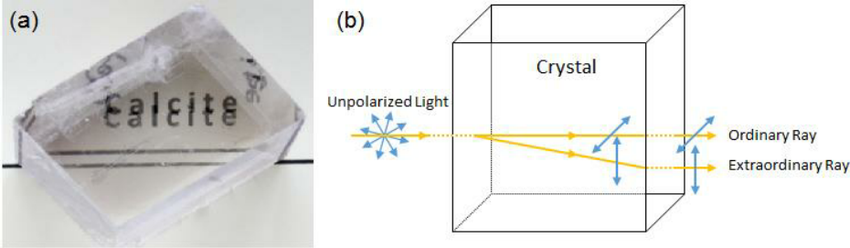

Calcite crystals are naturally occurring polarization analyzers. The best way to teach about polarization (at least, linear polarization) is to hand these out in class (along with a linear polarizer). In 2013, my then advisor Prof. Mike Raymer happened to be creating a pilot course for non-majors under the Science Literacy Program, called “Quantum Mechanics for Everyone”, and had asked Chris Jackson and me to help design and TA the course. Naturally, I accepted. And calcite crystals came in real handy there. Then it eventually came to designing a lecture on interferometry.

Prof. Mark Beck, in his book titled “Quantum Mechanics,” illustrated a very simple interferometer that can be constructed with these. So I bolted some components onto an optical table and went to work. The demo worked great. The students were particularly baffled by the counter-intuitive phenomenon of blocking light in one path to make light appear in another.

We had to buy big, clear, well-polished, research-grade calcite crystals from a commercial company. The half-wave plate inbetween the first two was required to reduce the path difference between the two arms to within the miserable coherence length of that cheap ebay diode laser. I also had to use a pinhole and several lenses to do some spatial mode filtering. My advice, just use a HeNe laser and avoid the whole mess.

LCD screen without polarizer

Liquid crystal displays are awesome for demostrations, since everyone has ’em (laptops, tablets, phones). As is illustrated in the image above, typically, and LCD module consists of an individually (pixel) addressable liquid crystal RGB (red, green, and blue) array sandwiched between two cross-oriented linear polarizers in front of a backlight. The liquid crystals are capable of rotating the linear polarization of the light inbetween by arbitrary angles, thus controlling the amount of light in each pixel (and color channel) that transmits through the front polarizer, thus forming any desired image. If you possess the fortitude required to take a metal blade to your LCD monitor, and the elbow grease to deal with the gunk that forms when cleaning organic raisin glue with acetone, then you can remove the front polarizer from an LCD screen and conduct the following demo.

Without the filter, there is no way to read the information on screen, since it is encoded in the selective polarization rotations at each pixel and color channel. Note that upon orienting the front polarizer at ninety degrees to the correct position, one can produce a negative of the intended image (focus on the girl’s eyes). This is because the RGB intensities get flipped. Also note that the native orientations of the linear polarizers are at 45^ˆ degrees with the screen edges. I suspect this is due to the rise of cellphones and tablets, which can be used in both portrait and landscape orientations. And people generally wear polarizing sunglasses. We wouldn’t want the screen to look blank when we hold the cellphone sideways now do we?!

Laser-pointer microscope

One of the easiest demos ever. Just point a laser pointer at a suspended water droplet and watch the projected shadow image. You should see silhouettes of tiny particles and/or organisms. For scale, you can use the spacing between the diffraction fringes around the silhouettes. Higher frequencies (UV lasers?) will have smaller wavelength and larger resolution. Some people online have managed to image moving creatures using pond water with these!