Quantum-shwantum

The Human Detector

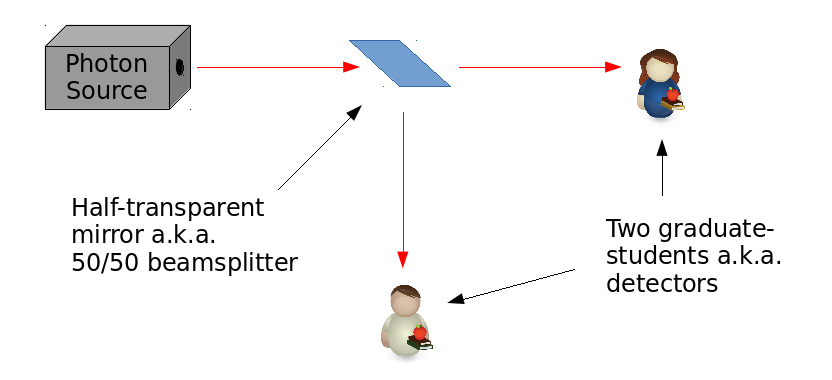

Consider the statement, “Human eyes can see single photons.” This has been the subject of research [1, 2, 3] ever since the term “photon” became common place in our scientific lexicon. There is a lot to unpack in that one claim. One possible approach could be to adopt a skeptical cynic’s viewpoint, and demand definitions. For starters, let’s just assume that “photon” is merely fancy jargon for “a weak amount of light that people can allegedly see with their eyes,” and exploit this provisional, functional definition to construct an experiment.

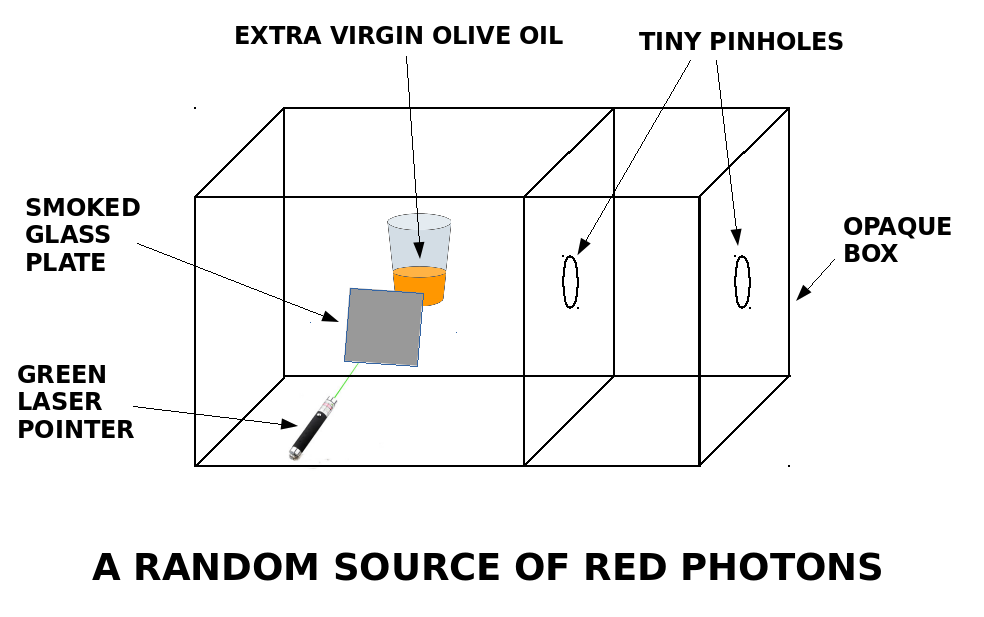

This wonderful image (above) was a 2014 submission by Vicente Torres-Zuniga (Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico) made to a photo contest held by the Optics and Photonics magazine. It demonstrates a wonderful phenomenon that I encourage the reader to independently verify, that shining a green laser pointer into extra-virgin olive oil will generate red light. If we were to decrease the intensity of the green laser by throwing some smoked glass in its path, this would predictably decrease the amount of red light generated. One could then package the whole assembly in a box with two collinear pinholes (covered with some red filters), and label the contraption a “Photon source.”

Of course, we would have to choose/tweak the opacity of the smoked-glass plate until the amount of red light escaping the box is feeble enough to allow us to use the term “photon” without getting funny looks. We can calibrate this by relying on a trusty graduate student, who has been forced to stay in a pitch-dark room for half-an-hour, and then has been instructed to let out an audible scream if they happen to see any mild flashes of light.

The typical scream pulse lasts for about a second. And the grad-student will need to inhale for about half-a-second before the next scream, which gives us an effective detector dead-time of about 1.5 seconds. To be safe, we can adjust the intensity of the source until we don’t hear two consecutive screams occurring sooner than a hundred dead-times apart (150 seconds) at a frequency higher than, say, once a day. The student could, in principle, be trained to change the pitch of his/her scream based on the color of the flash, thus approximating a low-resolution, human spectrometer. This proposal is still being reviewed by the University ethics committee.

Beam Splitting

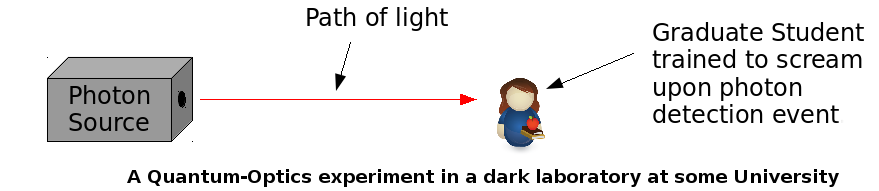

Any glass window that looks transparent when faced head-on, partially reflects light incident on it at a slanting angle. It is possible to manufacture glass that can reflect half the light incident on it, and transmit the other half through. In the lab, we call such optical elements “beamsplitters.” We can easily verify their purported property by employing two detectors, like in the setup below.

If we were to record the total number of times both Alice and Bob happen to scream in the above experiment, over the course of, say, an entire day, then for a perfect 50/50 beamsplitter, one would find that both their totals would be nearly equal (up to minor random fluctuations that are much smaller than the totals themselves). However, there is another quantity that could be recorded. Namely, the number of times the both of them happen to scream together (i.e. simultaneously, up to average duration of a scream). It turns out that this “coincidence count” actually depends on their relative distances from the beamsplitter.

We can perform a scanning measurement, by fixing Bob’s position, and starting Alice off at a location very close to the beamsplitter. If we were to measure the number of simultaneous screams per day, over several days, while asking Alice to step away from the beamsplitter a tiny bit at the beginning of each day, then we’d encounter a very strange result.

It turns out that the number decreases as their distances from the beamsplitter start to match each other. In fact, if Alice and Bob were to stand at exactly equal distances from the beamsplitter, then they would never scream simultaneously, no matter how many days pass. This seems to hint at the possibility of photons possessing some indivisible, particle-like nature. It is as if the beamsplitter is unable to split the photon into two halves, but instead sorts it into one path or the other with equal chance. This experiment opens the doorway for a definition of a “photon” that is somewhat more independent of the properties of it’s detectors.

Aside: Interestingly, this effect would completely disappear if we were to use a weak laser beam in place of the fancy, olive-oil based photon source. The laser data would simply flatline. The reason for this is beyond the scope of this article.

Interferometry

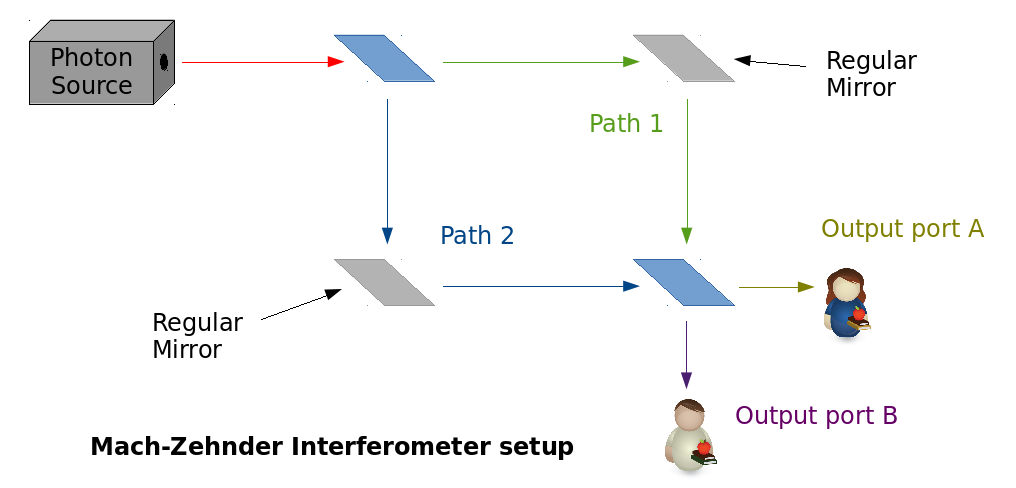

But, it gets weirder. Now, we will use two 50/50 beamsplitters and a couple of regular mirrors (those that reflect all the light incident on them) to construct the setup below. Here, the photons, upon encountering the first beamsplitter, would presumably travel via one of the paths labeled ’1’ or ’2,’ at the ends of which, it would run into the second beamsplitter, which would sort it into either of the output ports labeled ’A’ or ’B.’

This is commonly known as a Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Such setups were commonly used to demonstrate the so called, wave nature of light. If the light going in were set to be of a single color (wavelength) only, then the difference in lengths of path 1 and path 2 could be adjusted so that all the light would exit along only one of the ports, and not the other. The choice of exit ports can be tuned by adjusting the path-length difference. Here is a demonstration of that effect.

If we were to arrange our interferometer such that all the light would exit at, say, port B, then we would only hear Bob’s screams from the lab. Alice would stay silent, no matter how long one were to wait. So it would appear, that both the photons that took path 1, and the ones that took path 2, knew to turn towards Bob at the second beamsplitter. This, however, raises a conundrum. What would happen if one were to block path 1 with a brick wall?

It is easy to work out that half the photons would simply hit the wall and be lost to us. The second half would traverse path 2, and split towards either output ports with half chance. This would mean that both Bob, and Alice, would scream with equal likelihood (and never together). But consider this: How did the photons that made Alice scream know about the brick wall when they didn’t run into it? Wouldn’t they have turned towards Bob had the wall been absent?!

Entanglement

(Coming Soon)

Franson Interferometry

(Coming Soon)

On Language and Formalism

(Coming Soon)

Quantum Fields, and the Unruh Effect

(Coming Soon)